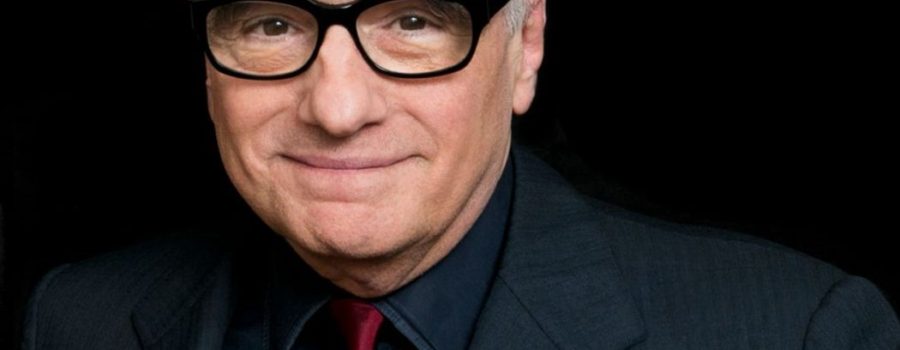

[Published at Film Inquiry] Martin Scorsese, arguably the greatest director in the history of cinema, was born on November 17, 1942 in Queens, New York City, NY to Charles and Catherine Scorsese, both Sicilian immigrants. Spending time in the garment district of Little Italy as a child and growing up in the Bronx among first and second generation Italians created an inseparable bond between Scorsese and his heritage, one of rich culture centered around family, food, arts, and, perhaps most importantly, class and gender roles. Italian-American culture is heavily patriarchal, particularly concerning the family hierarchy, a tradition that has remained strong throughout time.

Often sick as a child, Scorsese’s family would take him to the movies where he developed an infatuation with cinema. Since he couldn’t play sports, if he wasn’t at the movies, he was at home watching Akira Kurosawa films dubbed in English on the household television. If he wasn’t watching films on cable, he found himself renting reel after reel at his neighborhood rental shop. Thus began Scorsese’s lifelong passion for film preservationism. It was also at this time that Scorsese became heavily influenced by Neorealism, namely Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio De Sica.

The two filmmakers would vastly influence how Scorsese portrayed his Sicilian roots in his work; Scorsese was fascinated by the American immigrant story, in his case, as told through Italian and Sicilian Americans. Naturally, Scorsese’s interest in Rossellini and De Sica led to an exploration of filmmakers that they influenced, including Rossellini apprentices, Federico Fellini and Michelangelo Antonioni, Indian Bengali filmmaker, Satyajit Ray, and Swedish filmmaking legend, Ingmar Bergman.

Initially intent on becoming a Roman Catholic priest, Scorsese would forgo joining the priesthood for pursuing film at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, where he received a B.A. in English in 1964 and an M.F.A. in film in 1966. Scorsese cites that his Armenian-American film professor, Haig Manoogian, as a major influence on him, artistically and inspirationally, imparting upon him the drive that still fuels him today as a filmmaker.

Of course, these filmmakers are all legends of cinema, but they are not simply name drops. Each and every one of them shaped Scorsese’s thematic and stylistic focuses throughout his career. Stylistically, he drew from Kurosawa’s incessant need to be involved in every aspect of the filmmaking process including and especially editing, Ray’s character-driven scripts and slow pacing, and Antonioni’s expanding of the possibilities of film’s storytelling scope through elliptical and open-ended narrative.

Thematically, he drew the ideas of the importance of family and cultural preservation from Rossellini and De Sica, and derived his sense of existential struggle, questioning of faith, and ideas of societal isolationism throughout his films from Bergman and Antonioni’s body of work, as well as from his own objective critiques of the Catholic faith.

Add all of these ingredients together, and one of the world’s first film buffs-turned-filmmakers was born, one who would eventually make profound meditations about the banality of society, backwardness of his surrounding sociopolitical landscapes, films exploring sacrilegious and controversial views on faith, the Catholic religion, the importance of family, the deep roots of organized crime that thrived on impoverished Italian-Americans, and incredibly complex and honest deconstructions of masculinity.

Fresh out of college and finally equipped with the tools to transpose his introspective and existential observations onto celluloid, Scorsese would go on to make some of cinema’s most influential films comprising an unparalleled filmography. Martin Scorsese is living proof that The Academy Awards are merely a masquerade, not an honest reflection of cinematic talent.

Who’s That Knocking At My Door (1967)

Scorsese’s first feature film, Who’s That Knocking At My Door, was also the debut of fellow NYU Tisch School of the Arts classmate and friend, Harvey Keitel. It marked the beginning of a long and fruitful professional relationship between the two, as well as the first endearing cameo from his mother, Catherine, which would become tradition over the next few decades. The film is also significant because it was Scorsese’s first foray into two of his most prominent themes that would resonate throughout most of his following films: Catholicism criticism and flawed masculinity.

Keitel plays a devout Catholic named J.R., who meets a woman (Zina Bethune) he can see himself settling down with, but when he finds out she was raped by her previous boyfriend, he can’t handle it. He attempts to go back to a life of partying with his friends, only to realize that he still has feelings for the woman. After he tries to get her back, she rejects him for his judgement, prompting him to verbally degrade her as a means protecting his masculinity and ego. Eventually, J.R. tries to seek resolution by going to the church, only to find that it isn’t a solution, but rather, ironically, the root of his sexism and prejudice.

These are quite radical views from somebody who almost became a Catholic priest. Who’s That Knocking At My Door was only the tip of the iceberg of Scorsese’s exploration into what many religious people would deem sacrilegious observations. The theme of critiquing and questioning faith would come full circle nearly five decades later with his latest masterpiece, Silence (2016). Scorsese’s debut also marked the first collaboration of his legendary professional relationship with film school friend and editor, Thelma Schoonmaker.

Boxcar Bertha (1972)

Some film buffs may be wondering why Boxcar Bertha is on this list. It is often overlooked, and remains critically divided. Yet Boxcar Bertha was Scorsese’s ode to his Neorealism predecessors. Many of Rossellini, Vischonti, De Sica, and other voices of he genre’s films were funded by the communist party. Not the fascist, ideologically twisted communism of Lenin and Stalin’s dictatorships, but a purer form of communism, one more in harmony with Marxist theories. The communist party in Italy strengthened after Mussolini’s regime toppled over as WWII ended, it was, in that context of time and place in history, the liberal party.

Virtually every Neorealism film focused on the working class struggle, men and women fighting to financially support their families as they’re run out of business in their corporate- and commercially-shifting industries. Films like Paisà and Ladri di biciclette (The Bicycle Thieves, 1948) showed both the effects of a changing economy of uneven wealth distribution and the importance of unions for the working class to live comfortably.

Boxcar Bertha is a fictionalized autobiography, if you will, about Bertha Thompson, a Great Depression drifter, who runs into railway laborer and union leader and spokesman, “Big” Bill Shelly and two other working class men, Rake Brown, and Von Morton. The four of them become extremists in trying enforce unions to establish workers’ rights, revolting against the anti-union railroad tycoons to the point of murder and train-robbery. It doesn’t end well for Shelly, who’s referred to as a “Bolshevik,” furthering a theme of exploiting American propagandistic paranoia about anything Marxist-related.

The film introduced the world to Scorsese’s unmistakable fascination with cinematic violence, something that would become more visceral in his next film.

Mean Streets (1973)

Mean Streets is likely the first film that many Scorsese “newbies” may have heard of. It combines the theme of Catholic guilt seen in Who’s That Knocking At My Door with Scorsese’s most-explored subject of gangster life. The most autobiographical work of his filmography, Mean Streets was a reflection of events that Scorsese witnessed growing up in Little Italy as a child.

The film saw Scorsese reunite with his old pal, Keitel, but, most importantly, it was his first collaboration with the young Robert De Niro, a man who would become the greatest actor of his generation. De Niro’s career’s best work is arguably a result of working with Scorsese. He plays Johnny Boy, the wildcard and troublemaker of the group of lovable hooligans, establishing himself instantly as somebody with a natural aptitude for playing offbeat characters.

The dynamic duo arguably harbor the most harmonious director and actor relationship in the history of cinema. With Mean Streets, Scorsese used his Neorealism influences to apply the formula to a new generation, portraying realistic dialogue, reflecting the “street talk” of Little Italy gangsters, and a slice of life portrayal. Scorsese added his own spice to the formula, with quick-cut editing with seamless transitions, a consistent, surrealistic and lurid lighting, and innovative and precise camera angles, glides, and dashes. With all that jazz, this film set the precedent for the phrase, “quintessential Scorsese film.”

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that Mean Streets established Scorsese’s aptitude for compiling incredibly thorough, thought-out implemented and executed soundtracks, featuring hits such as The Rolling Stones’s “Jumping Jack Flash”. Many directors today, including Spike Lee and Quentin Tarantino, cite Mean Streets as one of the film’s that influenced their careers most significantly.

Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974)

“Wait, you’re really going to put Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore on this list?” You’re goddamned right I am; it’s a refreshing break from Scorsese’s naturally male-dominated perspective in his films. If for nothing else, it deserves to be on here for Ellen Burstyn’s (The Exorcist) lead performance alone, for which she won an Academy Award. But, alas, there is so much more to this film.

Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore shows the effect that men with skewed and destructive masculinity have on women, in this specific story, the titular Alice (Burstyn). She’s spent her whole life pleasing men, relying on them for happiness while she sacrifices her dreams of becoming a singer. Her deceased husband was an abusive drunk. After he dies, Alice and her son decide to pack their bags and hit the road from Socorro, New Mexico to Monterey, California. On their way, Alice has a brief romantic entanglement with an abusive married man (unbeknownst to Alice) named Ben in Phoenix, a situation which escalates, forcing Alice and her son to keep moving.

They end up in Tucson, where Alice gets a job at a diner, only to meet a seemingly charming man named David, who ends up to be just another abusive asshole. Finally, it is implied that Alice and her son make it Monterey to finally get the second chance Alice has been looking for, as a single, independent woman. On top of its laudable feminist perspective, the film also introduced the world to Scorsese’s obsessive fascination in dissecting outcasts of society through Alice and the eclectic cast of secondary characters. Speaking of outcasts…

Taxi Driver (1976)

Here we are, at the height of the golden age, where the “Movie Brats,” led by Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, John Milius, Brian De Palma, Steven Spielberg, Paul Schrader, and, the man of the hour himself, Scorsese, rule the era of New Hollywood. What is there to say about Taxi Driver that hasn’t already been said?

Not only is it Scorsese’s first cappolavoro, it is unanimously considered to be among the greatest masterpieces ever ingrained onto celluloid (oh yeah, get used to reading words like “greatest,” “best,” etc., because with Scorsese, in any context, those words are used often among film historians, critics, and filmmakers alike). Robert De Niro plays the unhinged ex-Marine, Travis Bickle. Fed up with the lack of morality (by Travis’s standards) in a post-Vietnam, heavily media-influenced era, personified by people he refers to as “scum.” Travis’s erratic behavior reflects the senselessness of an increasingly violent and immoral post-war society, filled with a lingering Vietnam guilt, Watergate, and political assassinations and attempts.

Travis has a plan to curb all of this putridness, and it’s an unsettling one. What starts out as a meditation about the devolution of American society through his repetitive narration and Scorsese’s slow pacing, turns into a maniacal, heart-pounding, pulsating thrill-ride.

De Niro’s turn as a well-intentioned but delusional man who can’t relate to anybody in his warped, fever-pitch perception of society, established himself as a force to be reckoned with, instantly solidifying him as a once in a generation acting talent. It is considered by some of cinema’s greatest voices to be among the greatest performances of all time. Furthermore, a 12-year-old Jodie Foster gives the most daring child performance in American cinema’s history.

New York, New York (1977)

New York, New York is an ode to the Golden Age of Hollywood and the Big Band Era of the 1940s, a time when men could virtually do whatever they want to women, especially in the entertainment busines. It is still Scorsese’s most sexist film to date, albeit not unintentionally so. The obvious standouts in this film are stage legend Liza Minnelli and De Niro, who not only learned to play saxophone for the role, but became astonishingly fluent in playing complex jazz melodies, going the extra mile, to say the least.

De Niro plays a confident musician who has a fixation with lounge singer, Minnelli. For an uncomfortable period of time during the first act, Minnelli clearly rejects De Niro’s come-ons; it is overtly apparent that she wants nothing to do with him. Yet, De Niro literally grabs her, physically bends her to his will, then adds some quick-witted, charming jokes to divert the fact that he has essentially repeatedly stalked and assaulted her.

The two end up together, for better or for worse, and also begin a fruitful professional collaborative musical relationship. However, Minnelli ends up in the spotlight, leaving De Niro behind. As much a deconstruction of the facade of the entertainment industry as it is one of gender roles in a historical context, New York, New York is a film that will please both Scorsese lovers and film lovers for its uncompromising peer into the politics of showbiz.

Raging Bull (1980)

Raging Bull is, again, virtually unanimously regarded as the best film of the 1980s, and it represents Scorsese’s most raw, in-depth exploration into the psyche of a notoriously tortured man with a dangerously wounded ego and distorted outlook on women. Based on boxer Jake La Motta’s life, the film earned De Niro his second Oscar (Best Actor in a Leading Role), and editor Thelma Schoonmaker her first. It was the first time that Schoonmaker had an opportunity to work with Scorsese since Who’s That Knocking At My Door; she was denied membership into the all-male Motion Picture Editor’s Guild for over 10 years due to inherent sexism within the institution.

It was De Niro’s most complete immersion into method acting, a technique he learned from his acting coach, the legendary Lee Strasburg. He gained 60 pounds of fat to play the older La Motta, trained rigorously to become among the top 10 middleweight boxing contenders in the world in real life (yes, you read that correctly), and lived with Joe Pesci, who played his brother, Joseph La Motta, for months before filming to develop a brotherly bond.

With only ten minutes of boxing scenes (shot all with one camera, an astounding technical achievement) in its 129-minute runtime, it was deemed by the American Film Institute (AFI) as the greatest “sports” film of all time, and made the AFI’s 10th anniversary list of “100 Years…100 Movies,” ranking as the fourth greatest film of all time. The film’s impact goes beyond cultural; it saved Scorsese’s life, and gave him a reinvigorated love for cinema. A passion project of his for years, De Niro finally convinced Scorsese to make the film while he was in the hospital after nearly dying of cocaine overdose. Credit for Scorsese’s newfound cinematic passion also goes to his fallen NYU professor and mentor, Haig Manoogian.

The film ends with the biblical quote, “All that I know is that I was blind, and now I can see,” referencing Manoogian. Scorsese dedicated the film to him “with love and resolution,” citing Manoogian as the man who helped him “to see.”

The King Of Comedy (1982)

Certain cinephiles may find this an odd choice for a Scorsese beginner’s guide, but The King Of Comedy was Scorsese’s first creative expansion into comedy. It also continued De Niro’s flawless record for playing oddball outcasts. He plays the psychopath, Rupert Pupkin, an aspiring comedian who believes an appearance on his idol, Jerry Langford’s (comedian Jerry Lewis in an endearing ode to himself) talk show will give him the fame he deeply covets.

As he begins to stalk Jerry, Rupert’s obsession spirals out of control. Eventually, he conjures up a bizarre plan to get himself on Jerry’s show, providing a decades-ahead-of-its-time commentary about America’s increasingly celebrity-obsessed culture. And by baby Jesus does it ring ever-more true today, as an emotionally stunted, xenophobic, and intellectually challenged reality TV talk show host and failed businessman named Donald Trump is now president of the United States of America. America, a culture that now associates celebrity with divinity, made this happen.

The film was largely misunderstood by critics at the time of its release, because the magnitude of celebrity obsession hadn’t quite registered on the sociopolitical Richter Scale quite as fully as it would in the coming decades.

The Last Temptation Of Christ (1988)

In a vast filmography filled with violence, rape, abuse, and biting cultural critiques, The Last Temptation Of Christ arguably remains the most controversial Scorsese film of all time. In the eyes of the Catholic Church, it is considered blasphemous because it dared to portray Jesus Christ (played by Willem Defoe) as a human being, not a divine instrument of god. Throughout the film, Christ is in a constant internal battle with himself, struggling to choose between his spiritual and physical convictions.

The film asks the question, did Christ die in vein? Though the film only depicts Christ fantasizing about having a life of material possessions and procreation with a wife and children, Scorsese’s honest critiques of his own faith in prior works provide a glimpse into his thought process in making The Last Temptation Of Christ.

The humanism of Christ, the reluctance of him to die for an unknown voice, sacrificing himself for the potential betterment of humankind as a questionable notion was extremely jarring to The Vatican, Christian extremists groups around the world, and many devout Christians. To say the least, the violence, sex, and the full-frontal nudity of Christ on the cross didn’t help the film’s reputation.

The Last Temptation Of Christ was either banned or censored in a multitude of countries across the globe including Argentina, Chile, Mexico, and, not at all surprisingly, the Armenian-genocide-denying Turkey. In fact, the film is still banned in the Singapore and the Philippines today. Apparently, attempting to portray Christ as simply a man with desires who was sexually active with Mary Magdalene, however more accurate it may be, historically, earned this the number six spot on Entertainment Weekly’s list of the most controversial films of all time in 2006. Governments can censor and ban this work of art all they want, it was and always will be a masterpiece. Speaking of masterpieces…

Goodfellas (1990)

Can you fathom that Goodfellas didn’t win a Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, or Best Film Editing Oscar? IMDb lists it as the 17th greatest film of all time. Furthermore, can you believe that Scorsese hadn’t won an Oscar yet, and wouldn’t for nearly another two decades?

It is important to establish that the Academy Awards mean absolutely nothing in terms of validity of art and skill. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (The Academy) went nearly 80 years before acknowledging minority actors and women directors, so their credibility, in that fact alone, is completely void. They love De Niro and applaud and award the performances that Scorsese exudes from his actors (including a Best Actor in a Supporting Role Oscar for Joe Pesci in Goodfellas), but refuse to acknowledge Scorsese. For such a liberal industry, The Academy is a starkly racist and conservative institution.

Goodfellas is Scorsese’s quintessential mob film, and what many consider to be the high point of his career (don’t worry, it isn’t, keep reading!). He takes cinematic feel of Mean Streets, updates it a generation, and combines visceral and disturbing violence with narratively quick-witted storytelling and endorphin-inducing stylistically dizzying camerawork. Think of Schoonmaker’s editing as the glue that holds an ambitious story of such scope in place. Always working side by side in the editing room with Scorsese, Schoonmaker manages to make the film visually and narratively flow to make cinematic magic.

Scorsese and Nicholas Pileggi’s screenplay (co-adapting his own novel) is filled with so many memorable quotes, it’s remained fresh to this day. Each different viewing of Goodfellas always brings a new visual or narrative nuance that was missed in previous viewings. Like a fine wine, the film gets better with age.

Cape Fear (1991)

Astonishingly, neither Taxi Driver nor The King Of Comedy were De Niro’s most unpalatable and twisted characters. Cape Fear, adapted from the original film starring Robert Mitchum and Gregory Peck, is Scorsese and De Niro’s most explicit fleshing out of a psychopath transposed on screen.

Again, De Niro plays the mentally ill, a convicted rapist, Max Cady, fresh out of the federal penitentiary after serving 14 years. Hellbent on seeking revenge on his defense lawyer who purposefully lost the case because his conscience outweighed his judicial duties, Cady terrorizes the councilor and his family, willing to go to any measure to bring him down. The film seamlessly walks the line between story and character development and shock value, often escalating in violence, sexual assault, and unsettling twists throughout the film.

Cape Fear is not a masterpiece, but it is a masterclass in building tension, accomplishing, at times, Hitchcockian levels of foreboding suspense. Scorsese always finds way to add subtle messages and support of film preservationism in his films. This time, he does it quite literally by using Mitchum and Peck as cameos, playing their original characters’ respective lawyer’s. Likely his most morally ambiguous film, Cape Fear still remains as shocking as it is thought-provoking.

Casino (1995)

Consider Casino Scorsese’s greatest hits, covering familiar territory with organized crime, its associated themes of dominance, gender roles, and greed, and its inevitable consequences. Pesci, De Niro, and Scorsese reunite for a successful third time. Casino was a critical success, and its rich screenplay served as a vehicle for Sharon Stone’s powerhouse performance.

Co-adapted again by Scorsese and Goodfellas author, Nicholas Pileggi, from his novel of the same name, Casino didn’t add anything new to Scorsese’s filmmaking palate, thematically. The film is filled with Scorsese’s now-ingrained, typical directorial stylistic flourishes and camerawork, particularly during gambling and interior scenes; he has a lot of fun choreographing the shots of the casino patrons, utilizing the setting as his playground.

One would think they’d be accustomed to Scorsese’s fixation with excessive violence by now, but Casino has some of the darkest moments among his films. You won’t soon forget, if ever, a certain scene involving baseball bats and a lot of bludgeoning. Also noteworthy about Casino is that it marked the end of Scorsese and De Niro’s long and fruitful collaboration. That is, until The Irishman, the upcoming mob pic about the death of real-life gangster, Jimmy Hoffa, set to begin filming in August of 2017.

Gangs Of New York (2002)

Gangs Of New York was a film that worked on several levels for Scorsese. It allowed him to explore the household themes that gangster epics cover, while uncovering the historical foundation of organized crime upon which his home state was built in the form of a period piece. Though a decent amount of his film’s have taken place in New York, Gangs Of New York is among Scorsese’s most heartfelt tributes to the resilience and diversity of the city.

Gangs Of New York was strengthened sizably by Jay Cocks, Steven Zaillian, and Kenneth Lonergan’s screenplay. The film, among other things, is about the immigrant story and the losing and rediscovering of one’s identity.

Zaillian’s (Schindler’s List) unique cinematic voice is fused once again with his incomprehensibly harsh roots. Armenians, among many other historically disenfranchised ethnicities, have endured their cultural identity and history being violently ripped from them, much like DiCaprio’s Irish immigrant character; their background was almost erased by the Turkish government in the Armenian Genocide. Lonergan and Cocks use their Irish-American heritage to provide the ethnic setting and accurate cultural landscape of the 1860s for the story, combining for three diverse perspectives to create realistic, intercultural dialogue in America’s first melting pot.

Gangs Of New York is pro-American because it celebrates immigration. Daniel Day-Lewis, whose acting résumé is unrivaled, gives one the best performances of his career as Bill The Butcher. He is so convincing as a hatchet-wielding, knive-throwing maniac, every other performance feeds off of his. Again, the fact that Day-Lewis didn’t win an Oscar for this film speaks volumes about The Academy’s credibility as the “end-all, be-all” measurement of cinematic greatness in the industry.

With Gangs Of New York, Scorsese found himself a new muse in Leonardo DiCaprio, who plays the main character in the film. It was beginning of a filmmaking relationship that would parallel that of Scorsese and De Niro’s a generation prior. Essentially, DiCaprio became the new De Niro. They would go on to make four more films together, the next of which would be their best.

The Aviator (2004)

Though this is a minority opinion, I consider The Aviator Scorsese’s best film of the 21st century, and certainly his best film since Goodfellas. As the genius airplane and filmmaking tycoon and eccentric billionaire, Howard Hughes, DiCaprio gives the best performance of his career.

Psychologically, it’s one of the most intense forms of method acting to date. Fueled by a multifaceted script from John Logan, The Aviator offers a brutally thorough and uncompromising look into mental illness. There aren’t many actors that could rise to the occasion in playing such a complex person (sorry, Warren Beatty).

DiCaprio immersed himself so deeply into the roll, that he nearly lost his mind, picking up old Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) ticks that he developed when he had it as a child. It registers frequency with so many wavelengths, that his performance makes the audience sympathize with a racist, sexist perfectionist with a troubling tendency towards anger.

Cate Blanchett helps soften the blow of DiCaprio’s Howard as the legendary Katharine Hepburn, in one of the best performances of the last 15 years. DiCaprio and Blanchett’s onscreen chemistry is electromagnetic, and Hepburn and Hughes’s relationship serves as the heart that carries the film’s 170-minute runtime.

The Aviator furthers the facade of The Oscars, and quite cleverly and subtly breaks the fourth wall in providing a glimpse into the larger facade of Hollywood itself. Sure, the film won five Oscars, including another for Schoonmaker and a well-deserved Supporting Actress Oscar for Blanchett, but Scorsese and DiCaprio were snubbed, yet again. First of all, the fact that The Academy still uses the term, “actress,” today is extremely problematic. Second of all, by this point in time, Scorsese would have at least 10 Oscars to DiCaprio’s three, if the Oscars were based on talent over politics.

The Departed (2006)

The Departed marked Scorsese’s sixth venture into gangster subject matter. Oddly, of all of his films, this was the one that earned him a Best Director Oscar. It was essentially an apology vote from The Academy, meant as a, “my bad, are we good?”. Even more astonishing is the fact that this story, adapted by William Monahan from Alan Mak and Felix Chong’s superior Mou gaan dou (Infernal Affairs, 2002), won an Oscar for its screenplay. A testimony to the diminishing originality among Hollywood studios today, the The Departed was adapted to tell the story of a Whitey Bulger-esque criminal in Boston.

Much like Casino, The Departed is a Scorsese greatest hits for the millennial generation, even including a staple Rolling Stones song on its typically rock-and-roll-infused soundtrack. It features the dazzling narrative reach and rapid-fire pacing of Goodfellas, a slew of familiar brawn, masculine characters, and Schoonmaker’s signature editing wizardry. Perhaps above all, this film is carried by the outstanding ensemble cast led by DiCaprio, Matt Damon, Mark Wahlberg, Jack Nicholson, Vera Farmiga, Martin Sheen, Ray Winstone, and Alec Baldwin.

The Departed is a good film, but it lacks originality, something rare in the source material that Scorsese usually chooses for himself. Yet, there is something comforting in it; it is reminiscent of a filmmaking era of the past. It introduced a new generation of casual filmgoers to Scorsese’s signature style.

Hugo (2011)

So, what’s all this fuss about digital these days? Scorsese, being a devotee of 35mm celluloid, decided to fully submerge himself into digital filmmaking technology with the IMAX 3D release of Hugo. On its exterior, Hugo is about another outcast, a young orphan without an identity who lives in the London train station.

Beneath the surface, Hugo is an impassioned ode to cinema, film preservationism, and plea to filmgoers of a new generation to carry on cinema’s great tradition. Scorsese has grown wary of a tired film industry that’s nearly unrecognizable to him, especially in its diminishing appeal to younger audiences. Approaching ten years since it was made, Hugo remains the best use of 3D today; Scorsese built entire set piece recreations of early 20th century London, including the train station, creating a fully immersive experience for the viewer.

As an added bonus, the viewer will be treated with a considerably thorough history lesson of the first 15 years of moving pictures pioneered by the Lumière Brothers, and the first auteur, Georges Melies, played with a tender hearth by Ben Kingsley. When the film isn’t exuding breathtaking visuals, it is developing its children characters, Hugo (Asa Butterfield) and Isabelle (Chloë Grace Moretz). Since working with the young Jodie Foster in Taxi Driver, Scorsese has proven time and again his ability to deliver outstanding child performances.

The Wolf Of Wall Street (2013)

The Wolf Of Wall Street is Scorsese’s ultimate critique of American consumerism and material obsession. Usually a backseat theme in his films, greed takes the pilot seat this time around. An extremely timely film after the 2008 stock market crash and housing crisis, the worst since The Great Depression, Scorsese’s biopic of the rise and fall of Wall Street stock-broker Jordan Belfort, played by DiCaprio.

Belfort personifies virtually everything that is wrong with America. He represents what society has devolved men to be in the current generation: greedy, racist, sexist, fiendish, careless, rude, violent, angry, oppressive. Though countless, thick-sculled fraternity boys across the nation overlooked The Wolf Of Wall Street’s narrative nuances and observations and championed it as their own anthem, using it as canon to justify and perpetuate their actions, the film’s message preaches the exact opposite.

The Wolf Of Wall Street is a cautionary tale about the less-flattering aspects of capitalism and the moral ambiguity it provokes. Very much a part of the entertainment and media industries’ “one percent” critique of the uneven distribution of wealth that Wall Street has caused, it is a film that helped give rise to Bernie Sanders’s presidential run.

The Wolf Of Wall Street is neither Scorsese nor DiCaprio’s best film by any means, but it marks the fifth successful collaboration between the director and esteemed actor.

Silence (2016)

Scorsese’s most recent film, Silence, is another masterpiece and further proof that The Academy Awards is a smoke and mirrors spectacle that skews the way validity and truths of cinema are perceived. Postponed over 30 years due to scheduling, money, and legal issues, it rounds out Scorsese’s religious trilogy, beginning with The Last Temptation Of Christ and continued by Kundun in 1997. It is considered to be one of his dearest passion projects.

Based on Shūsaku Endō’s novel of the same name, Silence centers on the true story of two 17th-century Jesuit priests (played by Andrew Garfield and Adam Driver), who embark on a journey to Japan to rescue their mentor (Liam Neeson). The protagonists find the remains of the Japanese Jesuits, 300,000 of whom once thrived, now living in small villages in fear, hiding from the ruthless Inquisitor (played brilliantly by Issei Ogata), who executes all those who don’t practice Buddhism.

With little dialogue except for Garfield’s whispery inner narration, long periods of piercing quietness, and sounds of nature combine to make a somber score reliant on white noise. It’s difficult to imagine a Scorsese film without music, until you see the beauty of the Taiwanese coast it was shot on (geographical similar to that of coastal Japan).

Unlike Scorsese’s recent digitally-shot films, Silence was shot on 35mm film. This brings a gritty realism to the setting and helps accentuate that classic vibe of the golden era for modern American cinema. This film is not without its controversy. Scorsese’s adaption of Endō’s novel takes several sacrilegious liberties.

As Ogata’s Inquisitor symbolically says in the film, the Japanese soil rejected Christianity. Their son of god was the sun, which rose every day. It was visible. Their paradise was tangible in nature and physical beauty. Of course, the refusal of the Japanese government to accept Christianity resulted in persecution, grueling details of which are shown throughout the film. These long, drawn out scenes are meant to reinforce in the audience how inherently fallacious it is to not accept others’ beliefs.

Depressingly but rather realistically, god doesn’t answer Garfield’s prayers in the end, a specific Scorsese addition.

Documentaries To Watch:

The Last Waltz (1978)

Widely considered among critics to be the greatest rock concert documentary ever made, and possibly even the best film about rock and roll in general, The Last Waltz focuses on the famous Canadian-American rock group, The Band’s last concert. On the most legendary rock tour in history, The Band had been traveling on the road for 16 years before they performed at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco on November 25, 1976.

Collaborative guests include many musical legends inspired by The Band such as Muddy Waters, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Van Morrison, Dr. John, Neil Diamond, Eric Clapton, Ringo Starr, and Bob Dylan.

Il mio viaggio in Italia (My Voyage To Italy, 1999)

Il mio viaggio in Italia is a four-hour documentary wherein Scorsese takes the viewer on a journey through the history of Italian cinema. For those unfamiliar with Italy’s rich cinema history, the most influential film movement in the medium’s history, Italian Neorealism, is discussed at length.

Half of the documentary covers the works of Roberto Rossellini, discussing the father of Italian cinema’s influence on both Scorsese and subsequent generations of film lovers and filmmakers alike. Other film’s included are those made by Rossellini’s contemporaries and apprentices, Vittorio de Sica, Luchino Visconti, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Federico Fellini.

Take A Breather, Then Get To Watching!

You’ve made it this far, now what? This Beginner’s Guide to director Martin Scorsese, one of cinema’s most influential voices, imparts upon you, the reader, the basis of knowledge to become not only a Scorsese buff, but an explorer of both the films that he influenced, and the cinema he’s influenced by.

Although there is a plethora of films to discover in this guide, there doesn’t exist a film helmed by Scorsese that isn’t worth watching. Exemplified by his five-decade-long body of work, his film’s offer intricate observations and critiques of American society, politics, Catholicism, immigration, organized crime, family roots, and unparalleled insights into male masculinity in the modern world.

Oftentimes a director can become too preachy, as his emotional connection can compromise his objectivity on the subject matter. Sometimes filmmakers fade in relevance and artistic achievements. Yet, Scorsese, even in the third act of his career, continues to evolve as a director and push his creative boundaries. Ever the person ahead of the industry he occupies, Scorsese fully embraces the inevitable industry shift towards digital distribution platforms.

Scorsese’s next film, The Irishman, will reunite him with two of his most famous collaborators, Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci, along with another gangster film legend, Al Pacino. The biopic will follow the events surrounding the death of gangster Jimmy Hoffa, and is set to be distributed by Netflix in 2018. Shot on a budget of around $100 million, it is over double that of Silence’s. Until then, you’ve got some work to do, readers!

What’s your favorite Scorsese film? Any favorites that aren’t on here (After Hours, Age Of Innocence, or others)? In your opinion, which theme or genre is he most adept at? Do you think Scorsese should stray away from gangster films, or are you excited The Irishman?

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.