[Published at Living Life Fearless] Daniel Dumile, most famously known as MF DOOM, although he went by a plethora of other rap aliases, one of the architects of hip-hop, passed away on October 31, 2020. His wife announced the news of DOOM’s “transition” on New Year’s Eve, capping off a year filled with heartbreak, loss, and tragedy. The fact that his death remained hidden from not only the public eye, but also his peers, for two months, remains on par with the mystique the legendary artist maintained about his personal life throughout his storied career. One of the greatest MCs to ever grip a mic – your favorite MC’s favorite MC – as the industry endearingly branded him, there is very little known about both Dumile the person and DOOM the artist. And that’s exactly how he would have wanted it.

His elusiveness wasn’t solely a result of hiding behind a mask – artists employ this technique fairly often (Sia, Daft Punk, Deadmau5), it was also because he was at once wary of an industry he consistently weathered despite the emotional battle scars it caused him, and fully entrenched in the supervillain persona he created as a result of this industry hurt.

One of the greatest MCs to ever grip a mic – your favorite MC’s favorite MC – as the industry endearingly branded him…

DOOM’s influence isn’t confined to hip-hop. Anyone who’s ever felt the desire to create can find inspiration in his flow. I was fifteen years old the first time I listened to MF DOOM rap, and I was never the same again. My way of thinking was fundamentally altered. His intricate rhyme schemes and clever alliteration and word play have substantially influenced me as a writer, both in my journalistic and screenwriting capacities. I often find myself conceiving of puns, arranging alliterative sentences, and even rhyming multiple words in a cadenced line, when appropriate, to more effectively substantiate a thesis or paint a scene, subconsciously paying homage to DOOM, occasionally even pondering what the reclusive artist would think of his vast reach on the cultural zeitgeist.

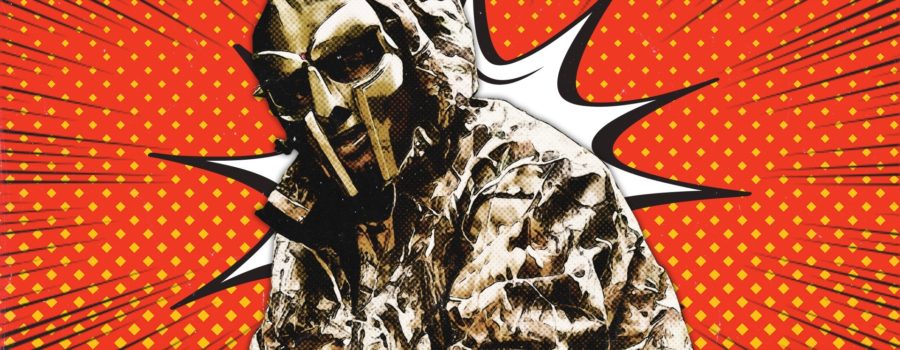

Indeed, I haven’t seen a death affect the entertainment world like this since, perhaps, David Bowie. Politicians, journalists, athletes, actors, and, of course, musicians came out of the woodwork to express their sorrow and support for the fallen supervillain, immortalized behind his Doctor Victor Von Doom-inspired mask (initially, it was a Doctor Doom replica, but eventually, a custom mask was designed by graffiti artist Lord Scotch by modifying a prop helmet from the movie Gladiator).

As aforementioned, we, mere bystanders of the destruction of prestige the supervillain left during his physical time here on earth, knew very few things about DOOM. We knew he belonged to a hip hop group called KMD with his brother DJ Subroc as Zev Love X. We knew that his brother tragically died. We knew that KMD’s label, Elektra Records, dropped the group the same week of Subroc’s death due to KMD’s Black Bastards album cover art, which depicted a graffiti-esque Sambo hanging from the gallows in a “live-action“ hangman game scenario. We knew that DOOM endured a period in the ‘90s marked by heartbreak and homelessness. We knew that, out of the ashes of despair, Zev Love X dawned the mask and villainous persona, becoming MF DOOM in the process, in order to swear revenge “against the industry that so badly deformed him,” he explained in an interview with All Music. According to Hershini Bhana Young in his book Black Performance Theory, we knew that, “Through a sampling of one of the best crafted comic book villains, MF DOOM positions himself as enemy, not only of the music industry but also of dominant constructions of identity that relegate him as a black man to second-class citizenship.” We knew that he employed vaudevillian-esque (the partial inspiration for the name, Vaudeville Villain – his third studio album, under his rap alias Viktor Vaughn), theater of the absurd techniques in the public spotlight, often deploying dummies, imposters, like a real-life supervillain, deeply immersing himself into his role.

We knew that “MF DOOM is the Andy Kaufman of hip-hop. He’s a supervillain.” According to Talib Kweli. We knew that DOOM was born in London, but grew up a New Yorker. We knew the Obama administration deported DOOM in 2010 after the rapper returned home from tour, stranding him in the UK for two years with visa issues before forcing him there permanently, both straining his career and leaving him with no desire to return to New York, the home that shaped him. We knew that his son, King Malachi Ezekiel Dumile, tragically passed away in 2017. We know that DOOM is survived by his wife Jasmine.

Split Personalities

DOOM wasn’t exactly human, in many respects, to his meticulously crafted liking. MF (Metal Fingers) DOOM, which he later changed to DOOM due to a creative character decision, was born on January 9, 1971 in London, England, to a Trinidadian mother and Zimbabwean father, and grew up in Long Island, New York. DOOM’s many alter egos mirror his splintered story of diaspora and societal acceptance common to many displaced Africans and other minorities. His complementing and conflicting personas include Viktor Vaughn, Zev Love X, King Geedorah/Ghidra, Metal Fingers (as a producer), Metal Face, DANGERDOOM (when collaborating with producer Danger Mouse), Madvillain (when collaborating with MC and producer Madlib), JJ DOOM (when collaborating with MC Jneiro Jarel), NehruvianDoom (when collaborating with MC and producer Bishop Nehru), DOOMSTARKS (when collaborating with MC Ghostface Killah), and Supervillian. Young explains that, “These names remix the names of popular cultural icons to create vibrant, edgy characters that express the rage and moan of black performance.” DOOM expressed Black pain through singular reworkings of massive popular culture icons. “King Geedorah, for example,” Young says, “is a three-headed space monster whose name alludes to the monster in Godzilla named King Ghidorah.“

He integrated them into his rap aliases, utilizing the characters to an almost method-acting extent…

However, DOOM didn’t flaunt these nicknames for clout. He integrated them into his rap aliases, utilizing the characters to an almost method-acting extent. For instance, as King Geedorah, DOOM’s rhyme scheme echoed in “threes.” He would rhyme in groups of three lines, consistently use three-syllable words, and reference the number three. As a Diasporic African, growing up in a multicultural household of South American and African immigrants, splitting time between two continents as he got older, one could infer that Dumile had to cultural code switch throughout his life. One could even argue that these ethnic, environmental, and sociopolitical factors also had an influence on the creation of DOOM’s collection of characters.

The Mask

Regarding the MF DOOM mask, Young writes, “An obvious trickster, MF Doom assumes the identity of a white comic book patriarch, blackening it in his quest for social justice. Through the interplay between comic book hero, flesh, and metal, MF Doom moves away from traditional liberal notions of him as human/black/artist.” DOOM didn’t want to be confined by stereotypes. “He rarely removes the mask in public for there is no real him underneath the armor…there is no authentic psychic interiority under MF Doom’s mask.” Young continues. “Rather, his identity is a complex interplay of flesh and machine, commodity and a voice that speaks for itself, outsider to the music industry society and an essential part of it.” It is important to note that DOOM never hid behind the mask. It was, among other things, a means of tuning out the unnecessary noise within the industry that affected him in the first act of his career.

Doom was the creator, writer, and director of this character, with complete creative mastery over how it was depicted in his music, the media, and among his peers. When Kweli asked DOOM whether or not he felt he was doing his fans a disservice by sending imposters to his shows, DOOM replied, “I’m the fucking supervillain. I’m not your friend. You don’t have to like me. You’re paying for the experience of dealing with a supervillain.” However, like any villain, DOOM didn’t see himself as the bad guy, but rather aptly, the industry and material rappers, focused on the excesses of fame as the endgame, as the true villains. “He’s the typical villain that you have in any story where a lot of people misunderstand him,” Doom said in a 2011 interview at the Red Bull Music Academy. “He’s always looked at as the bad guy, but he’s really got a heart of gold.”

I’m the fucking supervillain. I’m not your friend. You don’t have to like me.

Is it really so hard to understand why DOOM dawned the Doctor Doom mask? Not only does he cleverly re-appropriate a famously white character in order to make him Black, maintaining his villainy by multidimensionally infusing his own, unique life into the role, but he also reclaims what the industry, and society, at large, took from him: His identity – or identities – each one designed to destroy every MC that crosses its path. Doctor Doom’s story eerily reflects DOOM’s fall and hip-hop resurrection. Doctor Doom’s face was terribly disfigured in an experimental accident, after which he was exiled in Tibet, where he aimlessly wandered until monks took him in and rehabilitated him, teaching him their ways in the process. Doctor Doom repaid them by becoming their master, forging himself an armor of metal, and vowing to take revenge upon the world.

Similarly, DOOM was emotionally and mentally scarred by the death of his brother and firing from Elektra Records, subsequently spending years in “exile” in New York, wandering the streets, eventually finding the monk-like community of Doctor Doom’s origin story in the form of open mic nights across Manhattan. Welcomed by the rap community again, DOOM burst back onto the scene, dawning the masking and becoming the master of the hip-hop community that embraced him in this second act – the simultaneous protector of and wake-up call for MC’s under the material spell of the dark side of the industry – while vowing to take revenge on the industry, at large, that wronged him and other Black artists. An industry that notoriously takes advantage of its artists, particularly Black artists, without fully understanding the unique forms of expression that it represents.

Dawning the masking and becoming the master of the hip-hop community that embraced him in this second act…

That’s as much as anyone needs to know about MF DOOM. Most importantly, MF DOOM was adored by millions across the world. Public artworks and graffiti homages are popping up daily across every inhabitable continent. Although the mysterious rapper largely avoided the public eye, Dumile was dearly loved by his wife and his late son.

In honor of MF DOOM’s life and work, I compiled a list of my 20 favorite songs of the simultaneous industry outsider and essential hip-hop pillar, across several of his personas:

1. “All Caps” [Madvillain, Madvillainy]

2. “Sofa King” (Danger Mouse Remix) [DANGERDOOM, Occult Hymn]

3. “Rhymes Like Dimes” [MF DOOM, Operation: Doomsday]

4. “Hoe Cakes” [MF DOOM, Mm..Food]

5. “Accordion” [Madvillain, Madvillainy]

6. “Rhinestone Cowboy” [Madvillain, Madvillainy]

7. “Black Bastards!” [KMD, Black Bastards]

8. “That’s That” [DOOM, Born Like This]

9. “Lightworks” [DOOM, Born Like This]

10. “Old School Rules” [DANGERDOOM, The Mouse and the Mask]

11. “Benzi Box” [DANGERDOOM, The Mouse and the Mask]

12. “It Sounded Like a Roc!” [KMD, Black Bastards]

13. “Ballskin” [DOOM, Born Like This]

14. “Break ‘Em Off” [MF DOOM, MF EP]

15. “A.T.H.F. (Aqua Teen Hunger Force)” [DANGERDOOM, The Mouse and the Mask

16. “Doomsday” [MF DOOM, Operation: Doomsday]

17. “Hey!” [MF DOOM, Operation: Doomsday]

18. “Dead Bent” [MF DOOM, Operation: Doomsday]

19. “More Rhymin” [DOOM, Born Like This]

20. “Deep Fried Frenz” [MF DOOM, Mm..Food]

For any casual MF DOOM fans or MF DOOM newbies alike, may this sampling spark a quest of discovery for the vast discography of the supervillain. I implore you, immerse yourselves in the man behind the mask’s varied, multifaceted work. You won’t be disappointed.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.