[Published at Slant Magazine] While primarily known as an actor and activist, Riz Ahmed is also a rapper, and he often uses his music as Riz MC to call attention to everything that’s given rise to his activism. The narrative theatrical performance accompanying his 2020 concept album The Long Goodbye, which was livestreamed in February at San Francisco’s presumably haunted Great American Music Hall, posed three questions: “What am I doing here? Do I belong here? Did I make a mistake coming here?” The rhetorical queries confront the uncertainty of his present self through a reckoning with his ancestral past.

Bassam Tariq’s semi-autobiographical Mogul Mowgli, Ahmed’s first film since his Oscar-nominated turn in Sound of Metal, touches on generational trauma and the struggles of assimilation. Not only does it include a few songs from The Long Goodbye, it can also be said that it purposefully sets out to answer the aforementioned questions.

Ahmed, whose grandparents survived the partition of India and whose parents later survived Bangladesh’s war of independence, plays a rapper whose diagnosed with a rare degenerative illness and whose life is turned upside down as a result. His disease can be understood as the physical embodiment of his generational pain—a prime example of epigenetics, or how DNA is physically altered in response to our life experiences and those of our relatives.

Following the U.S. theatrical release of Mogul Mowgli earlier this month, I had the chance to speak with Ahmed about trauma, epigenetics, art as therapy, playing a character who parallels his personal life and history, workding with Tariq, and more.

As a descendent of Armenian Genocide survivors, I really related to Mogul Mowgli’s themes. What inspired you to want to tell this story?

We wanted to tell a story about the complicated relationship many of us have with the place we are from. That means family, or the hometown you outgrew, or your ethnic origins, your ancestral trauma or family expectations. Many people can relate to having this push-and-pull relationship with their roots, and for children of immigrants that is elevated.

We also wanted to make something that we wished existed but has never been seen on screen. Our stories, rather than me or Bassam Tariq telling other people’s stories. It was an attempt to liberate ourselves from performing for others, or wearing a mask to fit into people’s expectations, and just being ourselves in a way.

What was the writing process like with Bassam?

Bassam is incredible, and incredibly fast. He mixes comedy with horror with musical with drama, and puts a surreal spin on it. He’s one of a kind. And so collaborative. It was a joy.

In the film’s companion track, “Once Kings,” you mention the book The Body Keeps the Score, which covers the science of trauma, or epigenetics. What do you think Zed would say about using art as a vehicle for healing trauma?

I think for Zed it’s therapy, but he doesn’t quite understand what he’s healing. He’s using his art to understand and process his experience, but also to escape his true self and where he’s from by touring and performing a version of himself and his pain. It’s only when he starts creating in order to understand himself rather than performing to get the validation of others that he truly starts to heal. In my view, story is the greatest technology we have. It creates catharsis from trauma, and gives shape and purpose to our experience, in a way that allows us to persevere, to find connection and meaning in our greatest challenges. To me, the place we all belong is actually something we create—a culture, a piece of art, a story—that’s our home.

What did you bring from your own experience into this role? It must have been really interesting to play a character who performs and raps and is seen in the public eye.

Bassam pushed me to play someone close to myself, as he’s from a documentary background and he wanted me to take off my mask as a performer in the same way Zed is forced to. It was exposing and felt vulnerable, but also very freeing. At best, a role brings you closer to your core, even if you’re playing another character. This role did that.

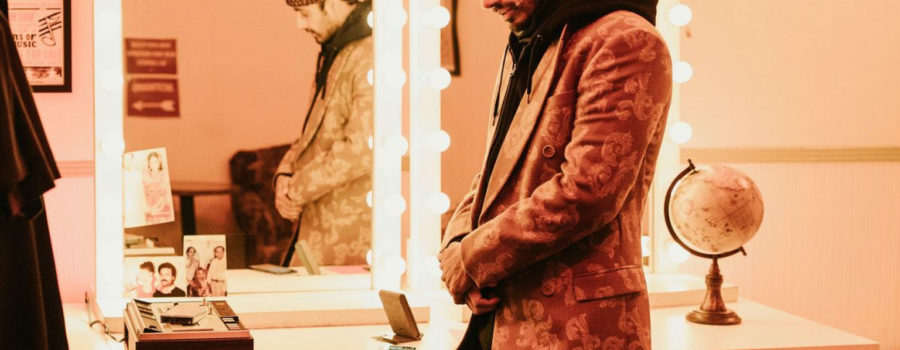

You and various characters alternate between clothing styles to honor your ancestors in both the The Long Goodbye narrative theatrical show and Mogul Mowgli. I’m curious to know your thoughts about the clothes in the film and the function they serve.

Clothing is an interesting element. The transformation of Zed’s hospital gown to Sindhi embroidered Kurta to Mughal style royal Anarkali by the end is about the power available to us in our heritage even as that heritage carries an immense and often paralyzing weight. The gift and the curse go together. We had a lot of fun with that.

Zed’s arc in the film is a tragic one. I saw this as an allegory for his generational trauma—a physical embodiment of his ancestral pain. Why did you choose a degenerative autoimmune disease to embody your character’s struggle throughout the film?

Diaspora [communities] suffer more auto immune illnesses than the general population. There are lots of theories as to why. One is that our bodies are playing out an identity crisis on a biological level. We don’t recognize or accept ourselves, and so we attack ourselves. We found that interesting, since Zed is in denial of his roots beyond paying lip service to them. So he’s at war with his DNA, in a way. In the end, it’s a story about self-love, but your idea of your self needs to extend outside of just your own body. Your self is built from things and people and events and ancestors that came before you, and those that will come after.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.