[Published at Slant Magazine] Writer-director Mike Mills brings a musicality to his films that recalls the early work of Jim Jarmusch and Richard Linklater. It’s no surprise, then, that Mills considers himself an amateur musician. His scenes play out on screen like poetic visual extensions of the songs and compositions that he chooses for his soundtracks.

Mills’s work often explores family dysfunction, grief, sociopolitical strife, and cherished parental stand-ins, using music as a way to unpack and move these themes forward through hypnogogic meditations and poignant memories—akin to an old home movie or a cherished family photo. Mills’s latest film, C’mon C’mon, encompasses all of Mills’s thematic greatest hits while continuing to showcase his impeccable ear for music in film.

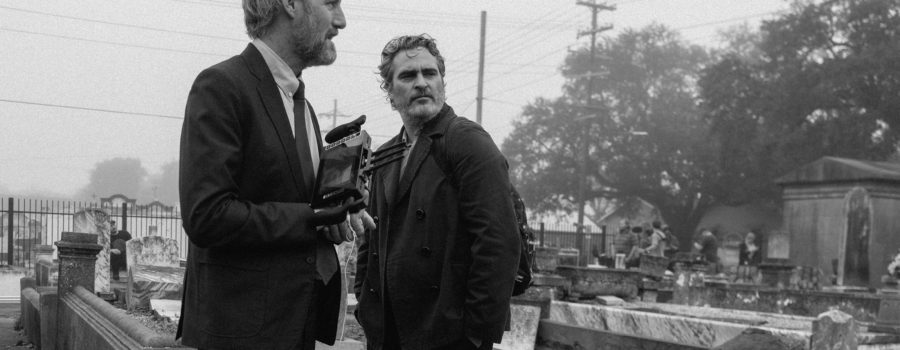

C’mon C’mon tells the story of a radio journalist, Johnny (Joaquin Phoenix), who must look after his nephew, Jesse (newcomer Woody Norman), as he travels the country working on a project about children and their hopes for and fears of the future. Like 20th Century Women, Mills uses his carefully curated soundtrack to establish an on-screen cultural backdrop—a dying bohemian culture crumbling at the foot of a capitalist wasteland—with composers Bryce and Aaron Dessner creating cloudy shades of vagaries within their score.

At the Mill Valley Film Festival last month, I had the chance to sit down with Mills on his home turf at the San Francisco Fairmont. Our conversation covered his experience working with Phoenix and Gaby Hoffmann, the themes that unite his work, the songs that he picks for them, collaborating with musician Elliott Smith during Thumbsucker, and more.

C’Mon C’Mon takes a similar approach to 20th Century Women, an optimistic story set in a pessimistic world. It also parallels that film through the way it views mothers as carrying the world on their shoulders as well as showcasing the hopes and fears of our children. Were these interviews improvised throughout the film, or were they written?

Yeah, they’re just documentary interviews with kids. Well, there’s a list of questions that I worked out, and also we would all talk about it together, me and Joaquin and Molly. But it’s a real interview, so they’re not just going down the list. So, like, “Oh, the kid says this, so I’ll follow that trail for a while.” And then, “The kid says that,” and then, “Oh, okay. Let’s talk about that.” So they’d meander all over the place, just following where the ball’s going. And Molly Webster’s really a radio journalist from Radiolab. Those are just very real interviews. And Joaquin’s skills of being present with and listening and all that were—he’s a great interviewer. And he listened. It was a lot, but he really also loved it, and we would do them often. We’d shoot all our bunch of scenes and do an interview or start the day with an interview and then do our narrative part of the movie. And it really infused the rest of the filmmaking. When you’re doing documentaries and start going into people’s homes, into their schools, it really changes your mindset. You had to be like you’re a visitor, and you’re listening, right? And it’s nice to bring that visitor-listening energy to your set.

Did Joaquin take some of your work in 2014 with MoMA and use your persona as a radio journalist as inspiration, or did he make it entirely his own?

So that’s how he prepared for the film. He just did interviews, and he hung out with Molly and just learned the gear. That was really important to him, all the stuff—that he had it right. And we talked a lot about Studs Terkel. Joaquin liked him and his vibe. Have you ever seen him? He’s a mean character. So, it got a little bit of Studs Terkel. And there’s a great radio journalist named Scott Carrier that Joaquin also really loved and listened to and got a lot from. But that’s very Joaquin to me. The guy who’s doing the interview, it’s a lot of Joaquin’s soul in there. He’s definitely channeling Johnny. He’s being Johnny, but it’s some combo platter. But Joaquin’s really, incredibly smart. And he’s a highly sensitive person to what’s going on in the room and the people and all that kind of stuff. He’s actually quite genius to be an interviewer.

You use expository sequences cut over music so beautifully, especially flashbacks and flash-forwards. What are some of your filmmaking inspirations?

Well, this film has something I’ve never done before. It’s not quite a flashback, but the story’s going along in a linear way, right? And then you’ll see something that happened in the past that you didn’t see before. So I don’t know what that’s called. It’s like that which you didn’t see that happened. So I guess that’s a flashback, but it feels a little different to me. It’s like some hidden part of the story, something that’s revealed to have happened. And that partly comes from Ermanno Olmi. He did this film called The Fiances that I really love. And there’s an amazing Hungarian guy named Szabo. He did a film called Lovefilm, and that really has influenced all my movies. And Fellini’s great at that. Often in a Fellini film, you’re like, “Where am I? Where am I in his sense of time?” Or time is very playful. Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima Mon Amour. He does that kind of stuff all the time. And it gets just very flowy and not about a text—not about a script. It gets more like music, in a way, I find. And I love music, and I find that I want to be a musician person. So, yeah, I like it when film language just takes off in a way that’s—irrational isn’t the right word—soupier than this normal narrative situation.

So, as a wannabe musician, do you have a significant amount of creative control over the songs that you put in your films?

Oh, yeah. I picked all of them. All the source songs are just songs I love or thought like, “That feels like it’s a Johnny—this record collection—or Irma Thomas when you’re coming into New Orleans. How can you not do that?” It’s like a part of writing to me, which songs you pick.

Grief almost plays its own character in this film. It both separates and brings Joaquin and Gaby’s characters back together, which I thought was fascinating.

My mom died when I was 33, and my dad died when I was 38. My kid saw an edit. My kid came in there and was like, “You did another movie about your parents dying?” I was like, “You are nine. Go be quiet.” Yeah, that’s kind of central to my heart or world. I keep circling that one. I keep coming back to that and how it does that. Just when someone dies, the way it impacts everyone around the person who died. Yeah. I think that’s what I do a lot, right? It’s not so much the person-who’s-dying’s perspective as the person around the person who’s dying.

And then grief takes you to your core. It reveals so many things that our normal, everyday lives cover up, right? It’s very unpolite, grief, in a great way. And there’s a lot of wisdom and almost hallucinogenic power to grief. I don’t know if you’ve experienced it. That’d be my description. After my dad died, I kind of felt brilliant. Really sad and wiped out but also really alive to the world and making connections that I don’t normally make and just feeling things in this really big way. It’s like you’re on mushrooms. You’re on grief mushrooms.

You mentioned a bit about what it was like working with Joaquin, but Gaby Hoffmann—

I love Gaby.

I feel like she doesn’t get enough starring roles.

Yeah. Totally, right?

She’s been around forever. So what was it like working with her?

Ah, she’s the best. It’s wild. It’s almost hard to direct her because it’s like, “You know everything I’m thinking. You’re smarter than me.” When someone’s smarter than you, it’s really hard to direct them because they’re already like, “I know everything you want.” But she’s so kind, so generous, a great comrade on the set, and now a great friend. Really like a team player and just awesome. But then when she’s in front of the camera, well, if someone’s that smart, you’re like, “How’re you going to be in front of the camera? How’re you going to let go and transgress and be wild and be feral?” But she does. I find her really alive in front of the camera, like a livewire. You just don’t know what’s going to happen next. She’s an uber movie star with an uber acting talent. I would love to see more form her.

Absolutely. Me too. C’mon C’mon is almost a spiritual sequel to 20th Century Women because of its theme of motherhood as the backbone of our society.

Yeah. I think that’s just how I feel. And Beginners too. That one, 20th Century Women, and this movie have a lot in common. My kid would say, “You’re very repetitive.”

Seems like your harshest critic.

Loves to razz. But it’s all with total love and fun. So, three of these movies are really interwoven in lots of ways because I’m writing about all these people I love and coming from this very known family space. They’re taking from the same soil, right? The plants are similar, right? Similar fertilizers, similar film interests. I love to take things that aren’t mine, like the Jimmy Carter thing or Harvey Milk. And I really love that style. I don’t experience time linearly. And I don’t think anyone does, really. So linear time, in film, I feel like is actually the most abstract, weird-ass, surreal thing. That’s the biggest construct—this causality of linear time. I’m really interested in that, and apparently I’m really interested in memory. Which is news to me, but, yeah, it keeps coming up. And, so, I feel really lucky I got to make these three movies, I have to say. I feel like I got away with something.

And Thumbsucker too. I think they all explore family dysfunction and normalize it. I don’t know what family isn’t dysfunctional.

Yeah, but I wouldn’t describe it as dysfunctional. Families have a very broad bandwidth from things you would describe positive and negative, but I really would avoid that dysfunctional word because it’s like, “Is that what you’re saying? What is functional?” And, actually, families are way more weird and feral and all over the place than they are in my movies. Real families. Real life is way more wild and hard to pin down than they are ever in the best movie in the world. The best documentary in the world is only a slice.

Great point. And speaking of Thumbsucker, you’re one of the few filmmakers who had an opportunity to work with Elliott Smith. What was that process like?

There wasn’t a lot of process there. I was supposed to do a record cover for Figure 8. And I did a whole bunch of work, and we really enjoyed each other, and we would go out for drinks once in a while, and we’d just talk about stuff, and we liked each other. What a beautiful, beautiful, beautiful person and body of work, right? So, I asked him, but it didn’t work out. He picked Autumn de Wilde’s picture. And Autumn’s a friend of mine. So it totally made sense. But when Thumbsucker came around—and Thumbsucker is really very influenced by Harold and Maude, and Harold and Maude clearly has all that Cat Stevens’s music in it—I asked Elliott to do the Cat Stevens song. And I wanted Elliott to do a couple other covers. And I was like, “Oh, well, that’d be interesting.” It was like four or five songs that are all Elliott Smith versions of a John Lennon song and stuff like that. And he was into it, and it was just like one conversation, like, “What if you did that?” I said, “Well, you try. You see.” And he’s a really quiet person. And a really gentle person. So then he went off to do that, and we knew that was happening. I was driving to the edit one day, and I heard like four Elliott Smith songs in a row, and I was like, “Oh, fuck.” You know what that means. You know that he’s gone. And so that was it. And so his version of “Trouble” was the one thing that he finished. He’s just another level of [talented].

Do you think Thumbsucker’s tone would’ve changed if Elliott had stayed in the film?

No. I feel like he’s still in there. I feel like the stuff we did with Polyphonic Spree has a similar heart to it. Of course, it would’ve been different. But it’s similar vibe to Elliott.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.