[Published at Living Life Fearless] Classic film remakes. One either loves or hates them. The two common sentiments seem to be either that if isn’t broke, don’t fix it, or that remakes can be a great way to introduce classic stories to new generations. Either way, there is often a considerable amount of controversy when a filmmaker or studio announces their plans to remake a beloved film. Such were the cases with both Luca Guadagnino‘s Suspiria and David Gordon Green and Danny McBride‘s Halloween remakes. Dario Argento‘s Suspiria (1977) and John Carpenter‘s Halloween (1978) are two of the most iconic and important entries within the horror genre in the history of film. Interestingly, both include early iterations of the “final girl,” a common trope in the horror genre, more commonly seen in the slasher subgenre.

Guadagnino and Green and McBride’s remakes redefine the final girl trope for a new generation, infusing their films with feminist overtones…

Breaking an age-old, deeply problematic tradition, Guadagnino and Green and McBride’s remakes redefine the final girl trope for a new generation, infusing their films with feminist overtones to avoid becoming yet another number added to the growing body counts of misogynistic undertones that have plagued the horror genre for so long. In this article, we will explore Halloween‘s roots in Giallo, the problematic nature of cross-cultural remakes, Green and McBride’s long road to bringing their new vision of Halloween to life, and how the two filmmaker friends threw the common notion of the final girl out the window.

The Modern Slasher’s Giallo Roots

The American slasher genre as we know it, today, would not exist without the Italian Giallo movement within film that rose to prominence in the late 1960s through the 1970s. Led by the aforementioned horror maestro Dario Argento, Giallo gained its namesake from the old, pulp detective novels with the yellow (“giallo” in Italian) covers by which the genre is influenced. Giallo films often featured a protagonist drawn into a murder or series of brutal murders (often seen from a first-person perspective, contained inexplicable twist endings and killer reveals, and often emphasized style over logic.

VCI ENTERTAINMENT

Argento’s L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage), released in 1970, was an example of one such genre film that includes first-person stabbing from the killer’s-eye-view, which was a visual style that John Carpenter would explore in Halloween. Indeed, Argento’s Giallo work the decade prior directly influenced John Carpenter’s Halloween in 1978, which, in turn, would influence the entire revival of the horror subgenre that is slasher in the decades to follow.

Imperialistic Roots Of The Hollywood Remake Machine

The need for the film industry in the United States to remake and Americanize every brilliant foreign film has only worsened over time as the breadth in Hollywood’s collective, creative cogs continues to dampen. The first superfluous American remake was that of Italian Neorealist filmmaker Luchino Visconti’s Ossessione (1943). Americanizing the themes, characters, and culture of a film is the ideological carryover of a country built upon imperialism, founded on capitalism, and the idea to take ownership of and monetize anything that is within reach. Tomas Alfredson’s Swedish masterpiece, Let the Right One In‘s (2008) shot-for-shot American remake was redundant, and Chan-wook Park’s Oldboy (2003) did not, by any means, require a Spike Lee revisiting.

SONY PICTURES HOME ENTERTAINMENT

It has become a trademark American act, repeatedly, throughout history, spanning not just film, but countless industries, inventions, philosophies, and sociopolitical movements: encountering things that aren’t ours and coining them as our own, in order to attempt to deepen our legacy and superiority within the context of history. In the context of film: Americans see a well-crafted foreign film, and still have that imperialistic desire, a seeming urge, to make it their own work of brilliance. If it isn’t to feed their own ego, they likely see a massive money-making opportunity. The brutal reality of this industry is that, more often than not, money will trump originality when projects get greenlit. Very rarely does one see other countries adapting American films for their audiences. Maybe the best way to remake a film, if it absolutely must be remade, is to not “outsource” talent, but rather to choose a filmmaker from the same country of origin as said original film that whomever the powers that be desires it to be remade.

The Path To Green & McBride’s Halloween

Perhaps it’s a blessing, then, that Green’s Suspiria remake fell through the cracks and into the hands of an Italian director. Green’s planned remake had been over 10 years in the making. Rumors of Green eyeing Suspiria began in 2006. However, it wasn’t until 2008 that his name was officially attached to the project, with Natalie Portman set to star. After difficulty securing rights from a protective Argento, who likens Suspiria to one of his creative children, Green finally obtained the rights. However, Portman went on to star in Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan (very much a Suspiria re-imagining in its own right) in 2010, and Green kept delaying the project due to contractual obligations.

BLUE UNDERGROUND

In 2015, the project ultimately found itself in the right hands with Italian director Guadagnino when Green removed himself from the project. Guadagnino would go on to remake Suspiria without Argento’s blessing, ultimately receiving favorable reviews. The Italian auteur would reinvent the final girl trope through a supernatural story and a fundamental change in the central character of Susie Bannion. Green would go on to choose the next best option as a film to remake: Halloween, the film inspired by Argento. With his writing partner, McBride (the star of his sophomoric feature directorial effort All the Real Girls in 2003), Green would reinvent the final girl trope in his own, creative way within the slasher subgenre.

So Long, Final Girl Trope

Whereas the original Halloween embraces the traditional final girl horror genre trope, focusing on Laurie Strode as the object and naive victim, the remake, which is actually a direct sequel that ignores the canon created by the plethora of others in the decades since the 1978 classic, focuses on Laurie Strode as the subject and all-knowing aggressor, literally played by the same actor, Jamie Lee Curtis. In the first Halloween, which was originally titled, The Babysitter Murders, Michael Meyers prefers teenage women as his victims. The surviving virgin in the final girl trope has served as an unofficial “rule” within the slasher subgenre for decades, acting as a cross-filmverse canon. Whether she is a virgin or she refuses drugs or other “societally unacceptable” behaviors for teenagers, if she maintains her moral purity, she will survive, while her morally inferior friends will fall victim to the killer. In the new Halloween, Michael Meyers doesn’t discriminate with his victims. He kills without pattern, preference, or thought. The only person he’s inexplicably drawn to is Laurie Strode.

UNIVERSAL PICTURES

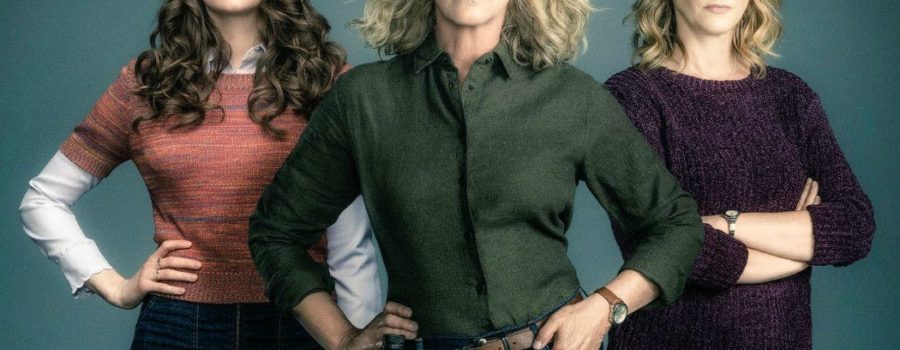

While the audience expects Michael Meyers to wreak havoc throughout Haddonfield upon breaking out of prison, he only kills those who get in the way of his pursuit of Strode. Since we’re conditioned, as viewers, to anticipate that Meyers will terrorize Strode and her family, it is, in fact, the other way around. Strode has been waiting for this moment since Meyers first attacked. Three generations of Strode women, empowered by Laurie’s ingenious booby-trapped house and fierce yearning for revenge, collectively dismantle Meyers (who, one could say, represents the archaic, patriarchal conditioning of society) in a thrilling climax, turning the final girl trope on its head. Meyers never stood a chance walking into Laurie’s death trap.

UNIVERSAL PICTURES

Laurie had Karen (Judy Greer), and Karen had Allyson (Andi Matichak), making Laurie and Karen obviously not virgins, thus morally “impure” by slasher genre standards. Although Allyson doesn’t explicitly engage in drug or alcohol consumption at the party her boyfriend invites her to, one can reasonably assume that she and her boyfriend are likely in a modern, millennial relationship, and thus are sexually active. And so, none of the final girl “rules” apply to any of the Strode women. Green and McBride purposefully made this a direct sequel to Carpenter’s original over four decades prior, ignoring the canon created by the flawed logic of the sequels, allowing them to create their own mythology that allows for a more feminist approach to the story.

The Rebirth Of The Female Heroine In Horror

The two major horror remakes of 2018, Suspiria and Halloween, were conceived from two sides of the same coin. Both reestablish a new vision for the final girl within the horror genre, but through entirely different narrative, thematic, and technical approaches. Perhaps this is a better way to approach remakes: the best person to remake and respectfully redefine an important film is likely somebody from the same country in which said original film was made. This makes for less potential for offensive cultural appropriation, inaccurate representations of culture, and a more accurate and authentic lens through which cinematic history can be paid homage to.

There are numerous callbacks to the Giallo genre that birthed the American slasher resurgence in the 1980s in Halloween, including Green’s use of the killer’s-eye-view, heightened primary colors through lighting in confined spaces such as a home, the inventive murders, a claustrophobic bathroom scene, and voyeuristic shots through unassuming neighborhood windows in throughout Haddonfield. Since he, ultimately, wasn’t able to remake Suspiria, it seemed only fitting that Green and McBride sprinkle in a few Giallo references and tip their caps to the genre that spawned Halloween‘s inception.

Since he, ultimately, wasn’t able to remake Suspiria, it seemed only fitting that Green, along with McBride, sprinkle in a few Giallo references…

As for Green and McBride’s answer to the problematic final girl trope that has cursed the slasher genre for so long? Three generations of women to refine the concept of the final girl(s) for a new generation of filmgoing audiences, not confined by a set of ridiculous rules or some dated, conservative, patriarchal moral conduct, thus resurrecting the heroine in the horror genre, one overly muddled with testosterone and misogyny. Suffice it to say, although Halloween and Suspiria were two of the most controversial remakes of 2018, they were also surprisingly refreshing, thematically speaking.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.