[Published at Film Inquiry] Is there anything this man can’t do? Actor and filmmaker Stanley Tucci undertakes his fifth directorial effort, and his first in ten years, with Final Portrait, a film about Alberto Giacometti (Geoffrey Rush), the esteemed and eccentric Swiss painter and sculptor. Based on James Lord’s (Armie Hammer) biography, A Giacometti Portrait, the film follows Lord, an art critic who flies to Paris for a rare chance to pose for Giacometti himself at his behest, offering a unique glance into the life of a genius in his natural habitat.

Do not confuse this as a biopic. In fact, Tucci told me himself, he flat out doesn’t like biopics; the idea of cramming somebody’s life into two hours is absurd to him, and, frankly, in Final Portrait’s case, I agree. Instead of a lifetime, Tucci picked an ideal period of Giacometti’s life, three intense, manic weeks with Lord. Through uncanny casting, powerful performances, minimalist and intimate directing, and a cinematography and costume design that combines for a wholly believable period piece, Tucci manages to provide more insight into a historical character than any other biopic ever has with Final Portrait.

Rush And Giacometti Go Hand-In-Hand

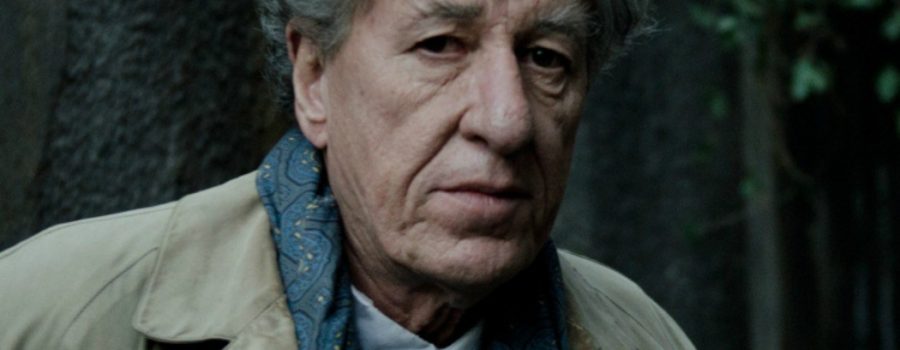

Giacometti is bold, confident, neurotic, and almost maniacally sharp, playing to Rush’sstrengths as an actor. Giacometti lives a bohemian and bourgeoisie lifestyle simultaneously, as he makes a fortune off his works of art which he hides in his studio, his sanctuary of madness and artistic brilliance. He decides his own schedule, when to work and when to play, living a life of leisure with purpose. Rush takes on this role with as much dedication as he gave throughout the film Quills, in which he plays The Marquis de Sade, another eccentric and controversial real-life artist. In fact, the two real-life historical figures share many traits, including their misogyny and how they provoke and push societal boundaries.

In Final Portrait, Giacometti’s relationship with his wife Annette (Sylvie Testud) is tested because of his protectiveness of his earnings and the fact that he focuses more attention on his mistress, Caroline (Clémence Poésy), than her. His relationship with his brother, Diego (Tony Shalhoub in his third feature film collaboration with off-screen friend Tucci), his artistic collaborator and moral support, is also unique because Diego has learned to accept his brother’s oddities, quirkiness and sheltering of his personal life.

Casting director, Nina Gold struck gold with Final Portrait’s cast, providing Tucci with more than enough talent to work with and bring out beautiful performances from the talented cast. Lord observes Giacometti keenly, writing down each detail, providing the groundwork of what would become Giacometti’s aforementioned biography. Giacometti’s daily routine is as follows: he goes out and parties with his prostitute lover, Caroline, late into the night, returns to his workshop and creates, and then proceeds to sneak in bed with his wife in the morning. It seems exhausting, but this is how he functions. Giacometti’s doubts and proclamations of how a portrait can never be finished alarms Lord, who constantly reminds him that he needs to return to New York.

A Total Bromance Triangle, Bro

As Lord spends time with Giacometti throughout Final Portrait, he realizes the aforementioned eccentricities are going to extend his time with the seminal artist, causing him to postpone his flight several times. Ever the polite gentleman, Lord keeps postponing his flight until it becomes ridiculous, all while Giacometti doesn’t care at all about anyone else’s life or routine other than his. This serves as a comedic yet essential aspect to providing insight into Giacometti’s process as an artist. The two often get sidetracked by Giacometti’s aloofness, frequenting the café, social functions and long walks through the cemetery.

Final Portrait is at its best when these moments alone with Rush’s Giacometti and Hammer’s Lord allow for mutually introspective realizations and revelations and eccentric onscreen chemistry, building their unique relationship. Tucci understands the importance of the two main characters’ connection, and lets these moments in the cemetery or at the café linger for as long as he wants. It doesn’t even seem superfluous to the story because their conversations are so captivating.

Over the course of Final Portrait, Lord also builds a relationship with Diego, whom he relates to because of their mutual frustration with Giacometti as an artist. Lord comes to realize that Diego was sucked into Giacometti’s world, his loyalty remaining strong, and that Diego has a sculpting talent of his own that he has kept at bay. Even while being overshadowed by his brother, Diego does not seem to mind; he goes with the flow, even eventually helping Lord wrap up this 18-day journey as a kind gesture to both Lord and Giacometti.

Impeccable Historical Accuracy

It is during the small moments in the film between Lord and Giacometti, who remains a man of few words most of Final Portrait, that we finally hear the artist articulate his opinion about art itself. He proclaims Cezanne the greatest painter to ever live, and even calls Brach and Picasso frauds and copycats. Those are bold accusations, but if anyone can make it, its Giacometti, who was badass enough to abandon the Surrealist Manifesto because of the limitations and confines it tried to put on art.

To provide historical context, Giacometti’s work is heavily influenced by Paul Cezanne, who was inspired by the movement of impressionism in painting, which began in the 1880s by Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Impressionism evolved into pointillism, characterized by the style of brush stroke, which evolved into Cubism, a movement indirectly founded by Cezanne which was indeed famously expanded by Pablo Picasso.

As so many artists were/are, Paul Brach was influenced by Picasso; the history of art, just like the history of time, repeats itself and recycles old material to add a new perspective. Giacometti criticizes his predecessors to Lord as much as he romanticizes them. He lives in the past, hence the reason why he holds so dear his older works of art and is disregarding and bitter about his newer works that are making him a fortune.

As the Final Portrait progresses, Giacometti slumps back to his old habits, becoming too preoccupied with Caroline, who comes and goes. Deep down, he fears most of his dearest works will be lost to lithographers, who tell him his paper is too old for the process to transfer onto stone. Though she is his muse and unhealthy obsession, Caroline ultimately deters Giacometti from his work. After a moment of self-actualization, the scatter-brained Giacometti refocuses his attention singularly on Lord’s portrait, finally…?

Art Preservation – Dear To Tucci’s Heart

After many comedic failures to capture Lord’s portrait over the course of two weeks, Lord finally gives Giacometti a deadline of four days, as advised by Diego, to which Giacometti agrees. Each day, Giacometti undoes the portrait created because he feels he can never live up to the standards he has set for himself. This is a fitting allegory to romantic ideologies present in the Final Portrait’s subtext, the idea that nothing can live up to the masterpieces that have come before it, that Tucci slips in with ease.

It is increasingly and hilariously annoys Lord, until he and the mischievous Diego conceive of a plan to end the cycle once and for all. It works, and Giacometti reluctantly gives Lord his final portrait, as this would be his last prolific work before his death shortly after. The portrait was sold last year for $20,000,000. Though Giacometti was fond of their experience and craved more time with Lord, even telling him to visit again, the two never saw each other for the rest of their respective lives.

There is a recurring theme of the importance of art preservation, and, by proxy, that of history. Art was once the only means of capturing a person’s image, long before photographs. Art is also a form of telling history, just as film is. Yet, painting is a dying art form, and Giacometti expresses his grief of this unsavory fact. It is also what fuels his doubts and neuroticism. Tucci shares the same sentiment. In fact, his father was an art teacher and professor, so Tucci grew up around painting and sculpting. For that matter, Hammer is a preserver of the arts; his great-grandfather was an art collector who had quite a few Giacometti’s that Hammer remembers seeing and handling as a child. Talk about full-circle.

There is also a theme of both misogyny and the complexity of love in Final Portrait, marriage and relationships. Giacometti cheats on his wife and ignores her when he pleases, yet she also cheats on him, and, for the most part, they are both okay with this concept. They have grown accustomed to each others’ lifestyles, a concept that Lord does not seem to wrap his mind around until the third act.

Final Portrait: The Perfect Film

In every aspect, Final Portrait is a perfect film. Tucci has been conceiving this project since his twenties, so he had time to craft the exact film he wanted. Every single shot, even if it came out of improvisation, was intentional and directed with a calculating precision. Much like Jackson Pollock’s abstract expressionist approach to painting, Tucci makes every blemish created by his extemporized directorial style deliberate.

During the premiere, Tucci explained at The Berlinale press conference that he wanted the color palate to be muted. Knowing it was a period piece, he did not want to create a sepia or black and white color palate seen in so many period pieces, but rather a realism with natural lighting. Giacometti’s workshop is a dungeon, yet, as soon as they leave for the café, the viewer notices a boost in primary colors in the color scheme, contrasting perfectly what occurs both inside the artist’s head and also in the world around him. The cherry on top of Final Portrait is the accuracy of the 1960s French Bourgeois outfits contrasted with the one suit Hammer brings on his planned short trip. Its characteristic of the style of the time: wider ties, belts, and lapels, and lengthier collars.

Furthermore, along with his director of photography, Danny Cohen, Tucci had two handheld cameras the entire film, providing a non-invasive and lifelike environment for their actors, allowing for more creative perpetuation and evolution during the filmmaking process. Tucci has undoubtedly evolved as a director since Big Night, 21 years ago, even after a 10-year hiatus.

It is wonderful to see Shalhoub and Tucci collaborating again. As a director, Tucci encourages spontaneity. He urges his actors to make things up, with Rush and Hammer both more than up to the task. As Hammer explained to me, working with Rush was like playing tennis with a world class, professional Grand Slam winner. Although Final Portrait is a film about perfectionism as portrayed through Giacometti, Tucci emphasized that he wanted to convey a chaos, paralleling the artist’s artistic process. In that sense, through some laugh-out-loud, tedious, drawn-out scenes of Hammer trying to hold his posture, an intensity and pleasant unpredictability is expertly woven into the narrative.

Keep Doing What You’re Doing, Mr. Tucci

One of Tucci’s more compelling characteristics is his nuance and self-control; he knows when the scene has come to a natural close, much unlike the film’s archaic central character. As such, the point of the abrupt yet beautiful ending of the film is that the painting of the portrait within the film ends because it had to end. Otherwise Lord and Giacometti would have been working on the portrait forever. Although, I could have watched another three hours at least, and, judging by the overwhelming applause at the Berlinale Palast premiere as the credits rolled, so could its intended audience: people who care about history. But, alas, to extend Final Portrait would be revisionist history.

Viewers should expect a delightful viewing experience in Tucci’s subtle, second directorial cappolavoro. Final Portrait is filled with acute passion and vigor, seamlessly-interwoven humor among the dramatic elements, a visually stunning history lesson, and superb acting that combine for another Tucci gem.

Do you prefer Stanley Tucci more as an actor or as a director? What is your favorite Giacometti piece? Do you enjoy art history? If not, Final Portrait may just cause you to. Tell us in the comments below!

Final Portrait was released August 18 in the UK, and is currently playing in limited theaters. For all international release dates, see here.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.