[Published at Awards Circuit] Oscar winner (and six-time Oscar nominee) Shirley MacLaine has been acting on the silver screen for over six decades. Daughter of drama teacher Kathlyn MacLain and sister of Oscar winner Warren Beatty, one could justifiably say that acting is in her blood. She was one of the spearheads who helped deconstruct an inherent barrier of sexism within the industry, one that is still prevalent today, but is making slow but steady progress. With only 75 credits in her filmography, she has been known to be quite selective, although later in her career, like many aging actors, her film’s have been somewhat inconsistent over the past two decades. That being said, there is never anything wrong with playing around with the occasional fun role to offset one’s more textured, multifaceted characters. With “The Last Word,” MacLaine takes on a more layered character crafted by first-time-screenwriter Stuart Ross Fink and director Mark Pellington (“Arlington Road,”The Mothman Prophecies,” “Henry Poole Is Here”). Pellington’s latest directorial effort creates a film somewhere in between some of MacLaine’s finer works (i.e. “The Apartment,” “Terms of Endearment”) and some of her more breezy films (i.e. “Rumor Has it…,” “Valentine’s Day”). Pellington’s career in film has largely been characterized by tonally uneven bodies of work, albeit ones that are commendably diverse in scope and subject matter.

[Published at Awards Circuit] Oscar winner (and six-time Oscar nominee) Shirley MacLaine has been acting on the silver screen for over six decades. Daughter of drama teacher Kathlyn MacLain and sister of Oscar winner Warren Beatty, one could justifiably say that acting is in her blood. She was one of the spearheads who helped deconstruct an inherent barrier of sexism within the industry, one that is still prevalent today, but is making slow but steady progress. With only 75 credits in her filmography, she has been known to be quite selective, although later in her career, like many aging actors, her film’s have been somewhat inconsistent over the past two decades. That being said, there is never anything wrong with playing around with the occasional fun role to offset one’s more textured, multifaceted characters. With “The Last Word,” MacLaine takes on a more layered character crafted by first-time-screenwriter Stuart Ross Fink and director Mark Pellington (“Arlington Road,”The Mothman Prophecies,” “Henry Poole Is Here”). Pellington’s latest directorial effort creates a film somewhere in between some of MacLaine’s finer works (i.e. “The Apartment,” “Terms of Endearment”) and some of her more breezy films (i.e. “Rumor Has it…,” “Valentine’s Day”). Pellington’s career in film has largely been characterized by tonally uneven bodies of work, albeit ones that are commendably diverse in scope and subject matter.

In “The Last Word,” MacLaine plays a onetime successful businessperson named Harriet Lauler, who decides to enlist the help of a young and adrift writer, Anne Sherman (Amanda Seyfried) to write her obituary to make herself look beloved. The film is at its best when it lets the audience remain a fly on the wall throughout Harriet and Sherman’s various comedic interactions. Seyfried matches MacLane, scene-for-scene, and the two create a wonderful onscreen chemistry. When Anne’s draft for Harriet’s obituary does not meet Harriet’s impossible expectations, Harriet sets out on a quest to change her past, bringing an unwilling Anne with her. What ensues is, essentially, a buddy dramedy. Harriet needs Anne’s help for a chance at redemption, while Anne learns and grows from being in the presence of the older, wiser version of her. If this story sounds familiar, that is because it is. It is a cliché character dynamic that has been told many times before throughout literature and film. However, there will never be a lack of demand for these types of stories; as long as film continues to maintain a staple of escapism in this increasingly disjointed and chaotic world, the majority of viewers find peace in a formula in which they know the outcome. What elevates these kinds of stories is the subject matter, character development, the context in which you place the characters within the story and the acting. Fink and Pellington succeed in two out of those four categories in relatively solid character development, particularly for Harriet, and fine acting. Accomplished actors Anne Heche and Philip Baker Hall also appear in the film as secondary characters, but are extremely underutilized and have no character depth.

Though her character is not as developed as MacLaine’s character is, Seyfried does her best with the material she’s given. The film belongs entirely to Shirley MacLaine, however. It is essentially a love letter to her achievements in film and helping to pioneer the film industry for women. Much like her character in “The Last Word,” she is a force to be reckoned with in cinema, and, as one of the film’s lasting messages underscores, her legacy will live on long after she’s gone. Harriet was an allegory, in some senses, to MacLaine; she was a business pioneer who, back in the ’60s and ’70s when sexism in the workplace was arguably at its worst, had to work twice as hard, be twice as smart, and achieve twice as many accomplishments. She did all of those things, but burning bridges on the way. The film does a decent job of exploring the shifting dynamics of a historically male-dominated workplace, one filled with sexism and prejudice through the lens three generations of women.

As part of Harriet’s quest to rewrite her own history, she feels that she needs to make an impact on the underprivileged kids. So, she befriends a young African-American girl, Brenda (AnnJewel Lee Dixon), to try and make a positive image of herself to the media. This is meant as an ironic plot point to reference Rudyard Kipling’s, “The White Man’s Burden,” which is a singularly Caucasian, ancient theory wherein white, imperialist countries see colonialism of “inferior” countries as a burden, albeit a necessary good. However, this allegory, meant to be comedic, comes off as off-putting, and, frankly, racist. Seeing an elderly white woman talk to a group of underprivileged women about how hard it was for her to choose to go to college, when a lot of these kids struggle to find regular meals for sustenance on a weekly, even daily basis. It was necessary to have a character of Brenda’s age to highlight the generational and cultural difference between the three female leads, but the means to introduce her character could have been done with more sensitivity or finesse.

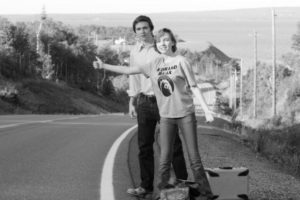

As a whole, the film is a tonally bipolar mess. Fink has a lot of work to do as a screenwriter, and Pellington either needs to find a new editor, figure out a consistent narrative tone or provide a smoother transition between scenes that illicit opposing emotions. There were unnecessary subplots such as Anne’s romance and the aforementioned misguided “white savior” subtext, and there were subplots that could have had more emotional weight and seemed more necessary to delve into to capture Harriet’s character arc more fully such as her lost of and longing for a return of familial connection and getting her professional reputation back after being unjustly publicly ousted and ostracized by her own company. The film does not become entertaining until the third act, where it feels like the whole film should have hovered in. We finally see Harriet, Anne and Brenda interact on a road trip of sorts, three generations learning from each other and bonding. If the film had begun here, it might have been much more watchable. What would have made even more palatable, was if “The Last Word” had a female writer and director as creative voices behind the project. That is what often holds a film down like this, particularly a duel character study through the perspective of two women; something is lacking in these characters, and it is simply the fact that the film industry is not going to evolve its ideas and grow to its fullest potential without women emerging as a more accepted voice, particularly in regards to female characters and themes. However, if you appreciate fine acting, this is arguably Shirley MacLaine’s best work in two decades, and, through her unyielding performance, she adds a quaint little exclamation point to her eclectic and storied career.

“The Final Word” is distributed by Bleecker Street Media, and is currently in select theaters.

GRADE: (★★½)

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.